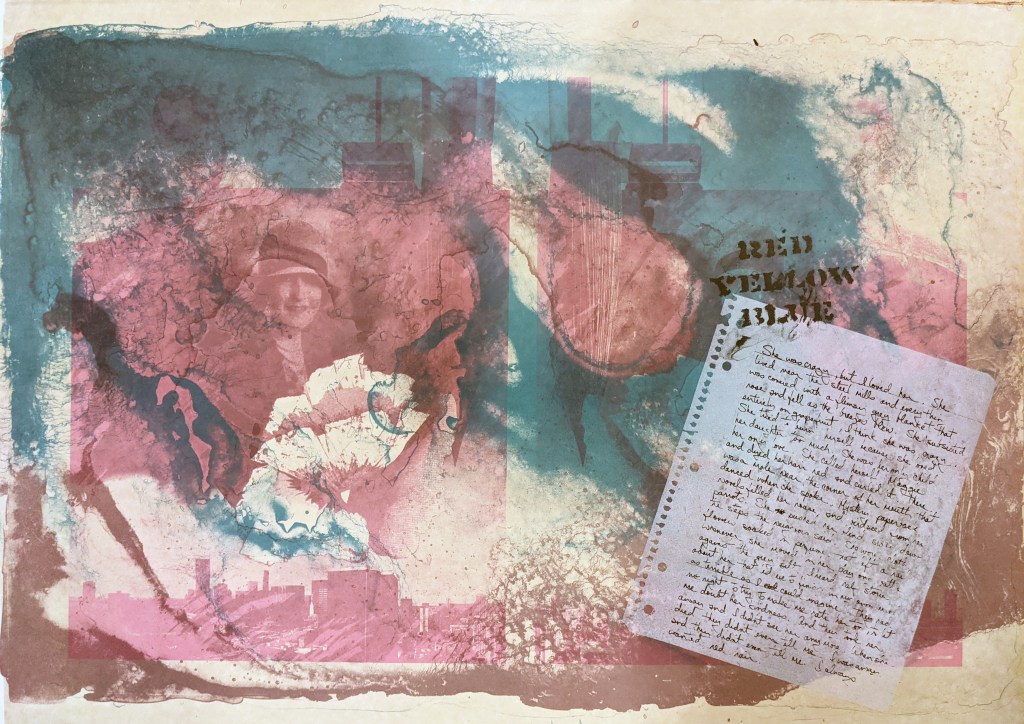

Photo: SC Martinez

Published in The Blue Mountain Review, September 2023

My thirty-year-old son sits across from me in the neighborhood diner. His hair is thinning at the front, but too long. He needs a haircut. At six months, he had a head of hair so thick it looked like an old man’s toupee.

I stumble into the emergency room, directed to a body strapped to a gurney, the face covered in blood, one leg splayed out at an unnatural angle. Who is this?

He smiles at a little joke he’s told me, and I see his straight even teeth, so different from his mouth as a two-year-old with milk teeth like a tiny comb.

A bloody hand reaches out to me with the tapered fingers and long thumb of a pianist. I shrink away from its coldness, but I know this hand.

He butters his toast and tells me about his week at work. His eyelashes are as long and dark as they were at birth, and they brush his cheeks when he smiles.

A neck brace keeps his mouth from moving. But I hear a faint voice say, I’m okay mom. I’m okay, don’t cry. It’s as if it’s come from a ghost.

I worry he works too much at his new job, striving to climb the rungs to the next level. As a toddler, he never sat down to eat. He always had an agenda, a project, a mission.

I need to cradle him. I need to count his fingers and toes and run my finger over his tiny ears, his nose, his mouth. But they take my baby away to the O.R.

I take his grownup hand in mine, squeeze it gently, and let go before he does. As a boy, he never wanted to hold my hand to cross the street, but I held it anyway.