Photo: SC Martinez

Published in Otherwise Engaged Literature & Arts Journal, Volume 16, Winter 2025

One morning, Carl received another in a long series of coded messages from the Dutch billionaire embedded in the text of the New York Times. He hinted that he would make sure that Carl’s upcoming job interview with a law firm would be a disaster. Carl had already been anxious about the meeting to be conducted on Zoom. In addition to his fear that his mental condition would be a deal breaker again, he was worried whether his good suit still fit since he’d put on a few pounds recently.

He tried to self-calm himself by resting his head against the pillows on the twin bed in his boyhood bedroom in Queens, decorated with fish wallpaper. He’d been happily living with his parents since he was fired from his last law job fifteen years ago. Carl detected the aroma of bacon, which signaled his mom was making breakfast. There was enough time to phone his friend, Hank, and share his concern over the billionaire’s persistent meddling in his affairs. Carl picked up his cell phone and clicked on Hank’s name.

Every day, Carl phoned Hank because he needed to hear his voice – a voice that always answered. Hank lived with his wife in Brooklyn. In truth, any voice on the phone line would have sufficed to help keep Carl tethered to the real world. Many people had filled the crucial role Hank now occupied during his life. The others lasted a week or two, maybe a month. Hank had been faithful. Without Hank, Carl feared he would disappear altogether.

But that morning, Hank didn’t answer even though Carl let the phone ring until voicemail picked up. Carl knew he couldn’t leave a message because Hank never bothered to set it up, even though it was easy enough to do. Carl traced his index finger around and around the edge of his cellphone case while watching his bedside clock count the minutes until he could again call Hank. He was probably in the shower.

In the early nineties, when Carl was twenty-five and single and Hank, a new father at forty, attended law school together, they didn’t socialize. Years later, they connected at an alumni mixer when Hank approached Carl, standing alone in the crowded ballroom. Carl never asked Hank why he spoke to him that night, but he was grateful.

Carl phoned Hank again.

“Hi Carl, sorry I missed you before,” said Hank. “How are you?”

“Terrible. I’m desperate. The Dutch billionaire is fucking with me again. I have an

important interview for an associate position at a major law firm next week.” “Use me for a reference.”

“I will. Since I successfully negotiated the Pakistani deal, the CIA hinted they are giving me five million and my parents another two million dollars. It’s going into my special needs fund.”

“That’s great, Carl,” said Hank. “That’s a big accomplishment.”

Carl was proud that despite not having a “real” job, he supported his parents and extended family with large amounts of money wired into their bank accounts from the grateful governments of a dozen countries he’d assisted.

“Carl, how do you know they’ve received the money?” asked Hank.

“They’re suddenly very nice to me, and they go shopping. They love to spend money. The CIA also hinted they may need my help with Iran again, but the billionaire found out. He put malware on my computer. I’ve lost all my valuable classified research.”

Before Hank could sympathize with Carl, the phone line went dead. Despite redialing every five minutes for the rest of the day, Hank never picked up. He stopped calling at eleven.

Carl’s mind churned over possible counterattacks to the Dutch billionaire’s next move, but in his heart, Carl knew he was powerless to stop him. With no digital access because of the malware, Carl felt utterly cut off from everyone, like he had in grade school when no one wanted to be his friend or invite him to play after school.

After a restless night, he neglected to take his medications, which modulated his mood swings. He became exasperated from his repeated attempts to contact Hank. In a blind frenzy, he smashed his radio with his old T-ball bat. When his parents left to shop at COSTCO, he made several trips to move his vast newspaper collection outside. He set it on fire in the backyard, which caused the NYFD to come to put it out before it spread to adjacent houses. With the radio destroyed and the newspapers burned to cinders, Carl prayed his torture would end.

As ordered by the firefighters, he stood on the back porch and watched the smoke billow upward in his parents’ backyard. He yearned for long ago when life was simple before he heard the voices and before the Dutch billionaire singled him out. Though Carl was secretly flattered he’d been chosen out of thousands of geniuses to work with the CIA, the billionaire’s manipulation of Carl’s day-to-day life was intolerable.

Since it was a nice day, Carl remained outside the rest of the afternoon. The fiery sunset, a sight he hadn’t seen in many months, left him with an afterimage he found comforting. He felt renewed. In a burst of optimism, he pulled out his phone and tried calling Hank again.

Hank answered on the first ring. “Hi, Carl. What’s up?”

In the past, Hank’s voice would have been enough to soothe Carl, but it had taken far too long to contact Hank. When Carl tried to reply, nothing came out.

“Are you there? Carl?” asked Hank.

The more Carl struggled to speak, the tighter his chest became. He blinked rapidly; his brain screamed, but no sound left his body.

“I guess I’ve lost you.” Hank hung up.

Carl hurled his phone into the side street and watched in horror as a Fresh Direct truck appeared out of nowhere and crushed it. His last lifeline was gone.

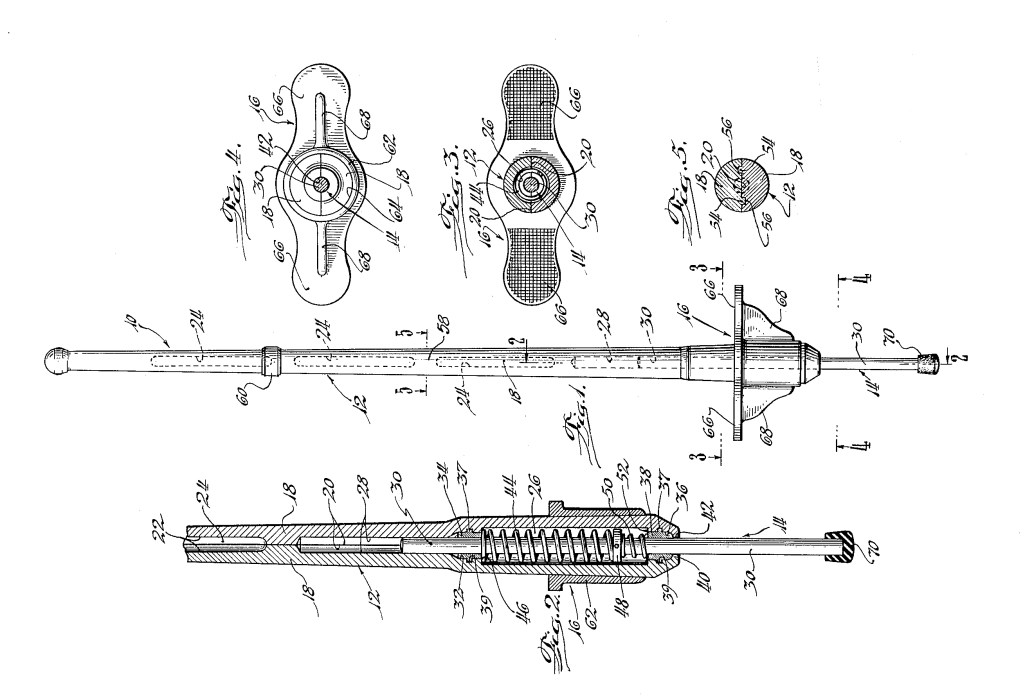

He stumbled inside and collapsed on his bed. Carl became transfixed by the shadow from the streetlight on his ceiling. It looked like a photograph he’d seen years ago when he’d worked briefly for the US Patent and Trademark Office as a patent examiner. He was researching bicycle parts and discovered a magazine story about a man who’d cycled across Africa and encountered human roadkill while crossing the desert. The article’s photograph showed nothing but sand as far as one could see on either side of the thin strip of highway. He wondered how long that person had laid there gradually pressed into the macadam by multiple vehicles and desiccated by the relentless sun into a humanoid stain as flat as an X-ray. Could a person no longer be a person but merely a shadow, unnamed and unheard? Exhausted by his eventful day, Carl’s eyes closed.

The next morning, Carl’s mother found him nearly unconscious due to a potassium deficiency. EMTs stabilized him. They detected an artery blockage and raced him to the nearest hospital with sirens that told Carl that Hank would contact him very soon and they’d be able to talk for a long time.

Carl was happy, resting on the gurney in the ambulance. He knew that Hank was still his friend and would always be because he once told Carl about his older brother, who’d also heard voices, received coded messages, and died far too young. Hank was dependable.