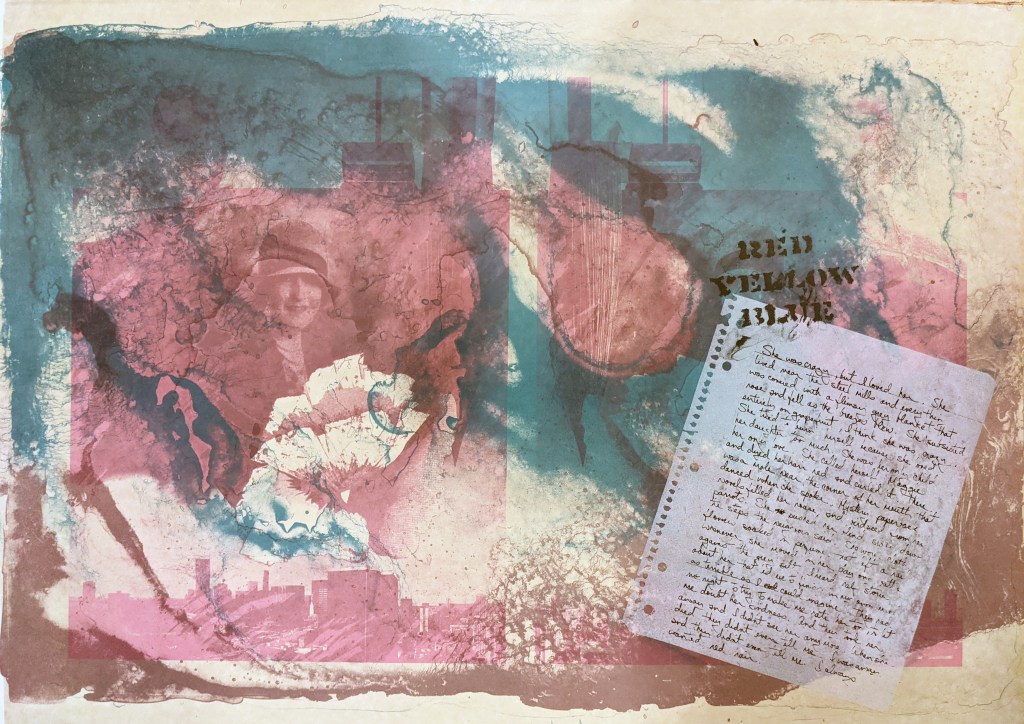

Photo: SC Martinez

Published in Wigleaf March 2, 2024

Click on link to read story in archives (03-02-24) Or read story below.

1

My sister found our parakeet, Hercules IV, dead on his back in his cage that hung near the telephone. Hercules, one in a series of less-than-robust birds purchased from the pet store at the strip mall, loved chattering whenever anyone was on a call. He’d learned to imitate the phone ringing, which caused frustration when one of us raced from the bathroom to answer it, or rather him.

My sister was eight years old and had not yet chosen a future occupation. Two years older, I was undecided myself. Our grandfather had died a few months earlier, and we’d attended the funeral. Possibly inspired by that experience, she announced her intention to bury Hercules. Our mother had no objection, having previously deposited Hercules I, II, & III in our kitchen garbage can.

My sister found a shoebox, wrapped Hercules in a sock that had lost its mate, picked wildflowers, and glued two popsicle sticks together to form a cross after sacrificially eating a frozen treat that stained her tongue blue. A few kids from the neighborhood attended the ceremony, which included a speech by my sister about Hercules’ brief though wonderful life, a moment of silence, and a rendition of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” with almost everyone chiming in. There was a scuffle over who would fill in the hole after she placed the box in the bottom which was settled after someone suggested everyone throw in a handful of dirt simultaneously.

(Click on number 2 to continue reading the story.)